To be a parent in the Lake Chad region today is to live with two permanent fears. The first is that you’re unable to provide your family with the most basic elements to ensure their survival – food, water, shelter and healthcare.

The second is that your family may be taken away from you in the blink of an eye, either kidnapped, killed or lost in the chaos. This is what happened to Saratu. When the sound of gunfire reverberated through the town of Baga, north-east Nigeria, everyone fled for their lives. They had no time to pack possessions.

Saratu’s mother searched for her children. She found Saratu alone and crying. She took her to the lakeside and put her on a boat with others escaping the fighting. She ran back to look for her other children. By the time she found them, the boat had already left with Saratu.

Governments and humanitarians are meeting in Berlin this week to galvanise the response to the humanitarian emergency in Africa’s Lake Chad region. The high-level conference comes one week after UK Prime Minister Theresa May visited Nigeria. While May’s visit highlighted the ongoing ties between the UK and Nigeria, very few people are aware of the humanitarian emergency in the north-east of the country.

Since 2009, conflict has crippled parts of Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon and Chad. Around 2.4 million people have been forced from their homes, some multiple times. It is one of the most complex, devastating and far-reaching emergencies in 21st century in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet it receives scant attention.

Decimated healthcare

In order to understand the situation, you need to look at the underlying issues. The lack of basic infrastructure, even prior to the conflict, meant that access to health care was limited.When fighting erupted in north-east Nigeria, healthcare workers fled and what few health facilities existed were abandoned. Many have subsequently been attacked – it’s estimated that more than half of healthcare facilities have been damaged. So you have a situation where an already weak healthcare system has been further decimated by violence. The result is an overwhelming demand for healthcare in areas that are difficult to access due to insecurity.

Climate change

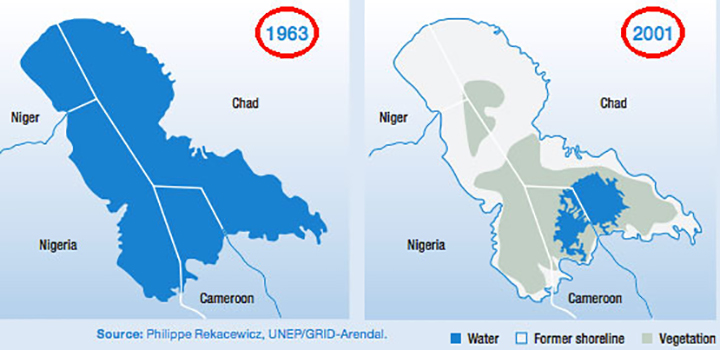

If you want to see how climate change can wreak havoc on lives, take a look at Lake Chad itself. The lake, which straddles the four countries, has shrunk by 90 per cent since the 1960s, in part due to climate change. The entire region is getting drier. Rains are irregular and farmers can no longer depend on them. This has given rise to cyclical malnutrition.

The insecurity in the region has compounded the food shortages. Fishermen can seldom access the lake, pastoral land has become unsafe, while farms have become inaccessible.

The upshot is that people can no longer provide for themselves and economic activity has ground to a halt. Lactating mothers and children under five are the most vulnerable. Emergency relief can help in the short term, but the damage has already been done. On one of my last trips to Nigeria, we visited villages where there were barely any children aged under five.

This is no natural phenomenon, no freak of nature. The truth is much sadder: most children under the age of five had simply perished due to a lack of food. Our focus, together with the Nigerian Red Cross, is to help communities provide for themselves: tools and seeds; cattle vaccinations, nets for fishermen; cash as capital for new businesses. With independence comes dignity.

African solidarity

Conflict, in short, has exacerbated an already dire situation. Yet the Lake Chad region is also a place of great humanity. More than 90 per cent of those who have fled their homes have been welcomed into local communities, communities that are among the poorest in the world. It’s African solidarity at its best and an example for the rest of the world to heed. It’s our job to support these communities as well as those who have been displaced.And what of Saratu?

Her story is intertwined with that of a lady called Hawa, who also fled Baga. As a refugee in Chad, Hawa took care of six children. Two were hers and four were children separated from parents. One day she found Saratu alone on a boat, crying. Saratu spent one year living in a makeshift camp under the loving care of Hawa. Eventually, the ICRC was able to reunite her with her step sister, using only names and photos.This is far from an isolated example. The Red Cross is currently looking for around 17,000 missing people in Nigeria alone, including 7,100 children. In Saratu’s story you have a microcosm of the crisis: indiscriminate violence; the flight to safety; families torn apart; resilience and survival; the best of humanity.

The pledging conference in Berlin is right to highlight the need to address the root causes of the crisis and a more joined-up approach to humanitarian and development programming.

Ultimately, however, what people need more than anything is peace. They want to stand on their own feet. We owe it to the likes of Saratu and Hawa to at least afford them the opportunity to do so.

Mamadou Sow is the ICRC’s operations coordinator for Africa. He tweets @MamadouSowICRC

INDEPENDENT

Sidebar

Magazine menu

Teline V

Best News Template For Joomla

Teline V

Best News Template For Joomla

27

Sat, Jul

21

New Articles